April 14-15, 1865: The tragic final hours of Abraham Lincoln

President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination is one of the saddest events in American history. Yet on the morning of April 14, 1865, the President awoke in an uncommonly good mood. One day less than a week before, on Palm Sunday, April 9, Robert E. Lee, the commander of what remained of the Confederate States’ Army, surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant, the commanding General of the Union. The truce reached at the Appomattox, Virginia, Court House signaled the end of the nation’s most destructive chapter, the Civil War.

To celebrate, Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln decided to attend the hit farce comedy “Our American Cousin,” which was playing at Ford’s Theatre. The Lincolns invited Gen. Grant and his wife to attend the play with them. At a cabinet meeting later that morning, however, Gen. Grant informed President Lincoln that they would not be able to join the first couple and, instead, would be visiting their children in New Jersey.

Even more ominous, the ornery Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, pleaded with the President not to go out that evening for fear of a potential assassination. Stanton was hardly the only presidential advisor against the outing. Mrs. Lincoln almost begged off, complaining of one of her all too frequent headaches. And even President Lincoln moaned about feeling exhausted as a result of his heavy presidential duties. Nevertheless, he insisted that an evening of comedy was just the tonic he and his wife required. Mr. Lincoln, confident that his bodyguards would protect him from any potential harm, shrugged off the warnings and invited Maj. Henry Rathbone and his fiancée, Clara Harris, to join them for a night at the theater.

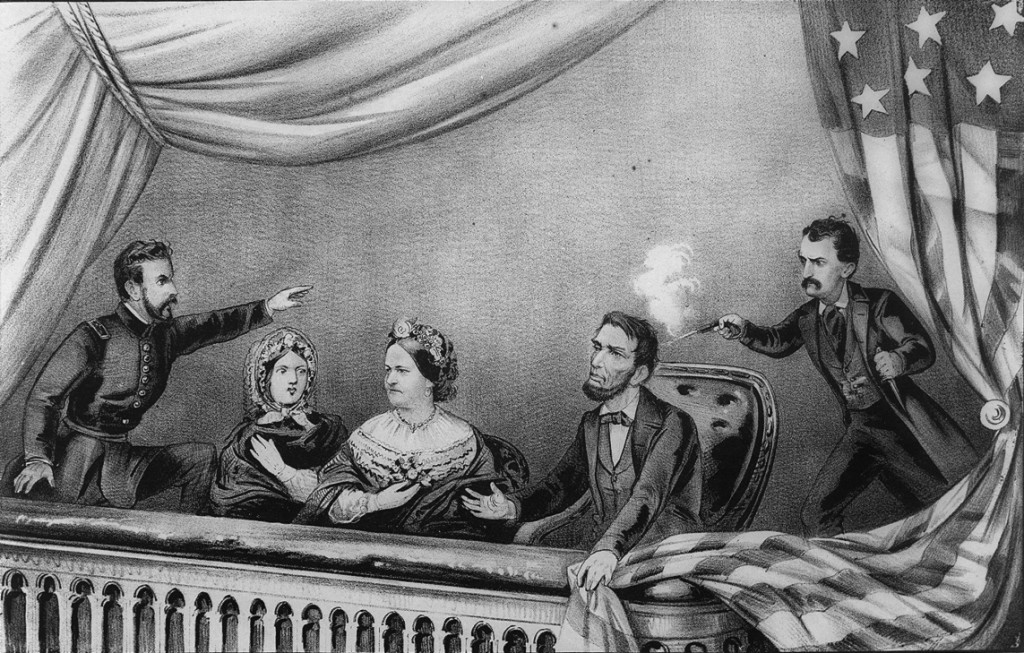

Lithograph of the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln. From left to right: Henry Rathbone, Clara Harris, Mary Todd Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln and John Wilkes Booth. Rathbone is depicted as spotting Booth before he shot Lincoln and trying to stop him as Booth fired his weapon. From the Library of Congress

Lincoln’s main bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon did not attend the play and, instead, John Parker, a police guard well known for his love of whisky, protected the president. Parker left his post outside the presidential box during intermission to satisfy an alcoholic craving at the nearby Star Saloon.

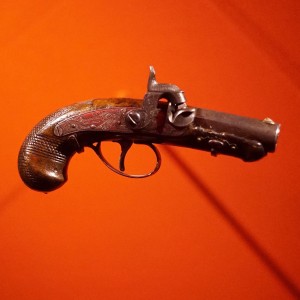

The Derringer pistol used by John Wilkes Booth to shoot Abraham Lincoln. Photo by Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images

During the third act, as the Lincolns laughed and held hands, a man barged into the unguarded box. The intruder, of course, was the actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth. The assassin discharged his Derringer pistol into the back of Lincoln’s head. Major Rathbone tried to tackle Booth down but the assassin overpowered him by slashing his arm with a dagger. Historians, as they are wont to do, bicker over whether Booth yelled “Sic Semper Tyrannis!” (“Thus always to tyrants!”) before or shortly after he shot the president (Aside from the controversy over the timing of Booth’s exclamation, some have claimed he said “The South is Avenged!”, “Revenge for the South!” or even “I have done it!”) We do know that Booth jumped from the box to the stage, caught his spur in the curtain, and may have broken his left shin (another source of contention among historians). He somehow managed to limp away and exit through the stage door, thus initiating one of the most intense manhunts in American history.

When it comes to medical history, however, it is not Booth’s injured limb that captures our imagination. Instead, it is the hours of agony the wounded president endured before finally succumbing early on the morning on April 15.

As members of the audience cried out that the president had been murdered and shouted pleas to catch and kill the escaping culprit, the first doctor to attend Lincoln was a 23-year-old Army captain named Charles A. Leale. He had just received his medical degree six weeks earlier, on March 1, from the Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York, widely regarded as one of the best in the nation. Leale was in the audience that evening after he learned that Lincoln, who he greatly admired, would be at Ford’s Theatre.

Ford’s Theatre, with guards posted at the entrance and crepe draped from windows, circa 1865. Photo by Buyenlarge/Getty Images

Dr. Leale immediately discerned, by sense of touch along the bloody wound, that the bullet had entered the president’s head just behind his left ear and tore its way through the left side of his brain. Sending out for some brandy and water, Dr. Leale recalled, “When I reached the president he was in a state of general paralysis, his eyes were closed and he was in a profoundly comatose condition, while his breathing was intermittent and exceedingly stertorous (i.e., noisy and laborious). I placed my finger on his right radial pulse but could perceive no movement of the artery.”

While examining Lincoln’s head, Leale’s fingers passed over a “large firm clot of blood situated about one inch below the superior curved line of the occipital bone” (at the rear base of the skull). The young physician removed the clot, wiggled his little finger into the hole made by the “ball” (the name for the round bullets then in use in the 1860s), and found that it had made its way into the brain. This maneuver may seem shocking to a 21st century observer but in the days before doctors knew anything about microbiology, let alone sterile surgical technique, it was a common practice for examining gunshot wounds. Dr. Leale quickly determined that this was a mortal wound.

After a few minutes, Lincoln’s breathing seemed to rally a bit and Dr. Leale was able to get a bit of the brandy and water down the president’s mouth. By this time, two other doctors, C.F. Taft and A.F.A. King arrived to the scene and the three of them decided to move the moribund president across the street to William and Anna Petersen’s boarding house, at 453 10th St. (now 516 10th St.) There, he was taken upstairs to rest in the room of a Union soldier named William T. Clark, who was out for the evening.

The macabre details of Lincoln’s last hours became far clearer in 2012 when Helena Iles Papaioannou, a research assistant working on the Papers of Abraham Lincoln Project, was searching through the “Letters Received” ledgers of the Office of the Surgeon General, which are deposited at the U.S. National Archives. It was in these files, under the letter “L,” that she found a 22-page report Dr. Leale wrote only a few hours after President Lincoln died. In fact, there are seven extant accounts by Leale, five dating from 1865, one from 1867, and another from 1909. Each version is similar, albeit each contains some variations and slight differences of terminology and tone. Yet many Lincoln scholars have deemed the Papaioannou document to be the most reliable version because it was written so closely after the actual events.

The room in which President Abraham Lincoln died, in the Petersen House in Washington, D.C., just across the street from Ford’s Theatre, circa 1960. The bed is a replica; the actual deathbed was acquired by the Chicago History Museum in 1920. Photo by Archive Photos/Getty Images

Given President Lincoln’s legendary height, he was placed on the bed in a diagonal position with “a part of the foot (of the bed) removed to enable us to place him in a comfortable position.” The windows of the room were opened and, with the exception of the physicians attending the president, his wife and son Robert, and several of President’s Lincoln’s closest advisors, the tiny room was cleared. The surgeons attempted to probe the wound by introducing surgical instruments (and their unwashed hands) into the bullet hole with the hope of extracting the lead ball and dislodged pieces of bone. Surgery of the brain being an all but non-existent medical specialty at this point in history, the doctors’ only hope was that by keeping the wound open, the blood might flow more freely and not further compress the brain, causing even more injury. Sadly, their efforts were to no avail, and as the morning hours proceeded, Lincoln’s course only went downhill.

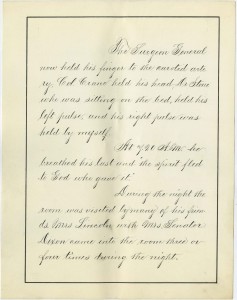

Dr. Leale wrote: At 7:20 a.m. he breathed his last and “the spirit fled to God who gave it.” Photo from National Archives

At 6:40 a.m., Dr. Leale wrote, “his pulse could not be counted, it being very intermittent, two or three pulsations being felt and followed by an intermission, when not the slightest movement of the artery could be felt. The inspirations now became very short, and the expirations very prolonged and labored accompanied by a guttural sound.”

At 6:50 a.m., Dr. Leale again recorded what he observed: “The respirations cease for some time and all eagerly look at their watches until the profound silence is disturbed by a prolonged inspiration, which was soon followed by a sonorous expiration. The Surgeon General (Joseph K. Barnes) now held his finger to the carotid artery, Col. (Charles) Crane held his head, Dr. (Robert) Stone (the Lincoln’s family physician) who was sitting on the bed, held his left pulse, and his right pulse was held by myself.

“At 7:20 a.m.,” he wrote, “he breathed his last and (here, Leale paraphrases Ecclesiastes 12:7) ‘the spirit fled to God who gave it.’” (Most historians give the time of death at 7:22 a.m.)

More famously, Secretary of War Stanton saluted the fallen president and famously uttered, “Now, he belongs to the ages.” (Some have argued that Stanton said “Now, he belongs to the angels.”) Stanton further eulogized President Lincoln with the apt observation, “There lies the most perfect ruler of men the world has ever seen.”

In a strange way, the events of April 14 and 15 represented the incarnation of Lincoln’s worst nightmare. Just three days before his death, Abraham Lincoln told bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon that he had a dream about a funeral that took place in the East Room of the White House. In the dream he asked a soldier posted near the casket, “Who is dead?” The soldier replied, “The President, killed by an assassin!” The President also noted, “Then came a loud burst of grief from the crowd, which woke me from my dream. I slept no more that night; and although it was only a dream, I have been strangely annoyed by it ever since.”

Dr. Leale went on to a distinguished career as a physician, after an honorable discharge from the U.S. Army in 1866 as “brevet captain.” He travelled to Europe and studied cholera during the great cholera pandemic of 1866. He married in 1867, fathered six children, successfully practiced medicine and worked on a number of charitable causes in New York City until his retirement in 1928 at the age of 86. But his greatest medical adventure occurred a mere few weeks after receiving his medical degree. That was the night and day, 150 years ago, when Dr. Leale took care of the 16th President of the United States, who drew his final breath early on the morning of April 15, 1865, because of the deranged act of a mad assassin.

Dr. Howard Markel writes a monthly column for the PBS NewsHour, highlighting the anniversary of a momentous event that continues to shape modern medicine. He is the director of the Center for the History of Medicineand the George E. Wantz Distinguished Professor of the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan.

He is the author or editor of 10 books, including “Quarantine! East European Jewish Immigrants and the New York City Epidemics of 1892,” “When Germs Travel: Six Major Epidemics That Have Invaded America Since 1900 and the Fears They Have Unleashed” and “An Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmund Freud, William Halsted, and the Miracle Drug Cocaine.”

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2eYmq6twMdomKmqmaF6coGMam9vbV2pv6KzyJxkpZmjqXqpu9SrqmaZkqeuqa3MZqOippOkua8%3D